Welcome back to Sellouts: 50 Years of Bestsellers, the feature where we pore over the best most popular fiction in America from the last half-century, one year at a time. (And if you’re not caught up, check out our piece on Erich Segal’s Love Story.)

*

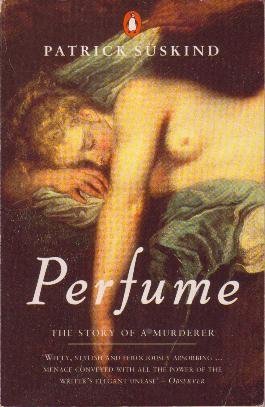

For the second installment of Sellouts, we’re hopping a flight to eighteenth-century France, the setting of Patrick Süskind’s Perfume: The Story of a Murderer. The novel came out in 1985, and in 1987 it won both the PEN Translation Prize and the World Fantasy Award (beating out Stephen King’s It). Perfume stayed on bestseller lists for nine years, elevating Süskind to international prominence as the most widely-read German writer since Thomas Mann. Translated into over 49 languages, to date Perfume has sold over 20 million copies worldwide, making it one of the best-selling German novels of the twentieth century. Despite its success, Perfume was the only novel the writer ever published.

Süskind has only allowed four interviews throughout his career (and the only English-language one I could find was with the New York Times in 1986). When he does speak, he seldom comments on his literary persona and claims to have such a poor memory that he can’t recall what he has read. It’s a useful handicap for Süskind to have, as it prevents critics from inserting him into any one school of thought. This also frees him from claims of plagiarism and allows his writing to exist as something born of the author’s individual genius.

This is a particularly notable trick for Süskind, as he believes plagiarism is necessary to write anything original. He used Perfume to explore “this type of modern man, this dark side of the Enlightenment” that emerged during the early 1800s. This “dark side” he refers to is the Romantic obsession with the mad genius archetype, which informed his creation of the novel’s protagonist. Yet by co-opting the style and tropes of the Romantics and applying them to an ironic magical realism story, Süskind created a wholly original novel. The result is a postmodern text liberated from the delusion of originality. Süskind thought Perfume would be an “absurd” literary experiment that appealed only to “people interested in history and literature.” The premise, in all fairness, is not typical for a best-selling novel.

Perfume starts in the “most putrid spot in the whole kingdom,” a street corner in Paris where a bastard is born and left in the gutter by his mother. Taken in by an orphanage, the boy is baptized Jean-Baptiste Grenouille. As a child, he displays an unusually strong sense of smell and memory for odors, so that when Grenouille walks the streets of eighteenth-century Paris, he memorizes the thousands of odors that “form an invisible gruel” over the city, an evocation brought to life by Süskind’s rich olfactory descriptions that often extend for several pages at a time.

The streets stank of manure, the courtyards of urine, the stairwells stank of moldering wood and rat droppings, the kitchens of spoiled cabbage and mutton fat; the unaired parlors stank of stale dust, the bedrooms of greasy sheets, damp featherbeds, and the pungently sweet aroma of chamber pots. The stench of sulfur rose from the chimneys, the stench of caustic lyes from the tanneries, and from the slaughterhouses came the stench of congealed blood. People stank of sweat and unwashed clothes; from their mouths came the stench of rotting teeth, from their bellies that of onions, and from their bodies, if they were no longer very young, came the stench of rancid cheese and sour milk and tumorous disease.

With these nauseating descriptions you can almost taste, Süskind wants us to know this is determinedly not the Paris of our contemporary cultural consciousness. This is Paris before the Haussman renovation, when city officials demolished the “overcrowded and unhealthy” medieval neighborhoods to make room for public parks, wide avenues, and homogenous apartment buildings. The Paris of Perfume is a vast labyrinth where disease spreads unchecked and wagons struggle through narrow, cobblestoned streets. This is the century when, rather than demolish Paris, city planners tried to banish foul odors that were thought to cause disease (another point of interest for Süskind). Boulevards don’t exist, buildings teeter at the banks of the Seine, and the Eiffel Tower is a distant dream. This is the Paris Victor Hugo lived in while writing The Hunchback of Notre Dame, a book designed to add value to the Gothic architecture that at the time was left neglected or destroyed. This is the cramped, filthy, malodorous Paris that Napoleon III would eventually deem unfit for modern civilization and gut. This is the Paris Süskind reimagined and appropriated in Perfume. This is where Grenouille adventures as a child.

It is while walking these streets that Grenouille discovers an odor so enticing that he is certain “unless he possessed this scent, his life would have no meaning.” He tracks the scent to its source and finds a girl of thirteen or fourteen.

But since he knew the smell of humans, knew it a thousandfold, men, women, children, he could not conceive of how such an exquisite scent could be emitted by a human being. Normally human odor was nothing special, or it was ghastly. Children smelled insipid, men urinous, all sour sweat and cheese, women smelled of rancid fat and rotting fish . . . [But] her sweat smelled as fresh as the sea breeze, the tallow of her hair as sweet as nut oil, her genitals were as fragrant as the bouquet of water lilies, her skin as apricot blossoms, and the harmony of all these components yielded a perfume so rich, so balanced, so magical, that every perfume that Grenouille had smelled until now, every edifice of odors that he had so playfully created within himself, seemed at once to be utterly meaningless. This one scent was the highest principle, the pattern by which the others must be ordered. It was pure beauty.

Grenouille strangles the girl, lays her on the ground, tears off her dress, and smells her “under her chin, in her navel, and in the wrinkles inside her elbows.” As someone with no odor of his own, a “nonsmell” that revolts everyone around him “the way a fat spider you can’t bring yourself to crush in your hands disgusts you,” Grenouille is compelled to memorize the girl’s smell. When he leaves the body behind, he’s finally found his life’s purpose: to “revolutionize the odoriferous world” with her “delicacy, power, stability, variety, and terrifying, irresistible beauty.” He plans to use her odor to become “the greatest perfumer of all time” and create “an angel’s scent, so indescribably good and vital that whoever smelled it would be enchanted and with his whole heart would have to love him, Grenouille, the bearer of that scent.” His motive makes the sudden violence oddly sympathetic: after a childhood of abandonment and isolation, Grenouille commits murder in a quest to make others love him, to “rule the hearts of men.”

Given the novel’s success, studios naturally wanted to turn Perfume into a movie. Producer Bernd Eichinger first tried to obtain film rights to Perfume in 1985, but Süskind refused to give them up due to his being entirely averse to publicity: all he wanted was to disappear into his work, rejecting the notoriety that young artists typically crave. Süskind even wrote Perfume in secret—his friends and relatives only learned about the book when it began to appear in installments in the Frankfurter Allgemeine.

Süskind did finally sell the film rights in 2000 for 10 million euros. The producer paid for it with his own money, as the studio wouldn’t pay the exorbitant sum. The film, however, turned out to be only a shadow of the book. While the crew recreated eighteenth-century Paris with precision, the visual medium was unable to capture Grenouille’s interior world, stripping him of the obsession and humanity that defined his character. While Perfume is, undeniably, a difficult book to translate to screen, the film still grossed $135 million. (And true to form, Süskind was not at the premiere.) Perhaps it’s only fitting that the movie would do well: after all, what’s the harm in seeing a reproduction of a book when the source material is already co-opting a previous style of art?

After the movie came out, the French perfumer Thierry Mugler reproduced the novel’s fifteen olfactory themes in a limited edition box set. The perfumes included in the box set were Baby, Paris 1738, Atelier Grimal, Virgin Number One, Boutique Baldini, Amor & Psyche, Nuit Napolitaine, Ermite, Salon Rouge, Human Existence, Absolu Jasmin, Sea, Noblesse, Orgie, and Aura. Only 300 sets were produced. They sold out in Europe in a week and cost $600 each. They occasionally appear on eBay for more than double their original price. Everyone, it seems, wanted more of Perfume: they wanted not just to see the book on the big screen, but to live inside the sensory world of Grenouille. To understand what compelled his lifelong obsession.

The book, it seems, has compelled a plagiarism all its own. While scent is central to Süskind’s literary style, Süskind’s writing became, briefly, central to the perfume industry. Few literary books achieve such success that they’re reconstructed in our reality. Once it was written, Perfume had something to say to a vast audience: we love reproductions. We love what is familiar, and will pay to live inside, if only briefly, the worlds that our most beloved artists have created. By creating a vivid fantasy of eighteenth-century France, Perfume lived on, and will continue to live on, with no need of its author. That is its final plagiarism.

BRIANNA DI MONDA is a contributing editor for Cleveland Review of Books. Her fiction and criticism have appeared or are forthcoming in The Brooklyn Rail, Litro Magazine, and Chicago Review of Books, among others. She was nominated for the 2021 PEN/Robert J. Dau Short Story Prize for Emerging Writers.