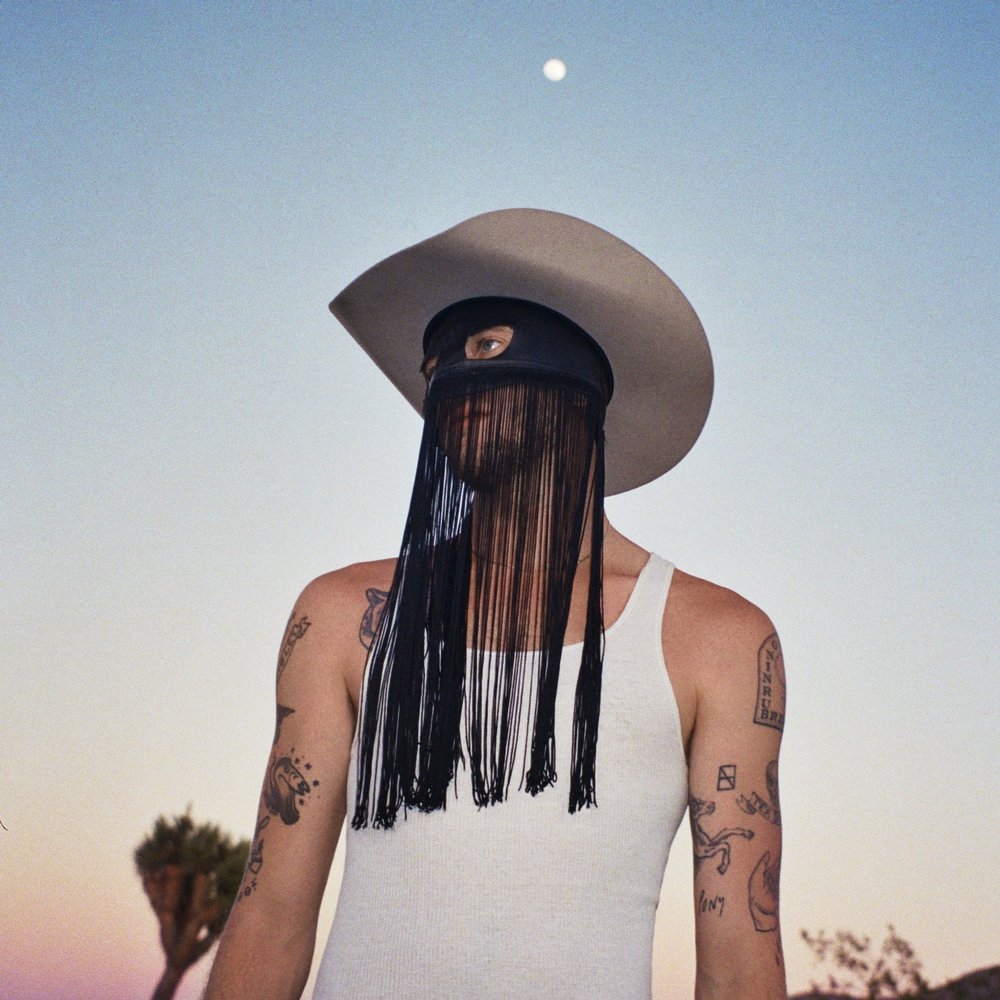

It’s early November 2020 and I cradle my iPhone in my apartment living room listening to Orville Peck’s performance of “Drive Me Crazy.” I clicked the video upon seeing the thumbnail of Peck brandishing his signature fringed mask. He’s my gay cowboy action figure. White shirt and pants. Black boots glinting in the golden light of the carousel around him. Like anyone watching Peck perform, I’m drawn to his fringed half mask he never removes—the way the tassels flutter as he strides and empties himself into the microphone. In his mystery, he becomes a vessel for the queer love song. A romance between two truckers whose story exists across radios and double-lane highways.

I watch the video over and over, not just for the melody’s beauty, but also for the complexities of queerness Peck’s work opens for me, a queer person living alone and often isolated in rural Pennsylvania at the time. I connect to the way Peck’s work makes palpable rural and “country” queer longing. I become somehow simultaneously both the lovers in the song and, then, as the story ends, I become once again aware of the messenger, the masked cowboy cradling his acoustic guitar and tipping his hat.

Immediately, I type into Google, “Who is Orville Peck really?” I feel a slight amount of guilt for the impulse to unmask him, but I brush that away for the sake of curiosity. Now, I wonder what that impulse means. An immediate need—the voice in my head asking, “Who is he?” What piece of this person did I want? The urge seems to run counter to what I love about being a queer person and what queerness means to me.

Often, I tell people, “I like the word queer both for my gender and my sexuality because it makes me feel free.” I love the capaciousness. The room to permit my gender and sexuality to fluctuate. And most importantly to me, “queer” permits me to be uncertain about those categories. José Esteban Muñoz talks about queerness as “not yet here.” In the introduction of Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity, he writes, “We are not yet queer. We may never touch queerness, but we can feel it as the warm illumination of a horizon imbued with potentiality. We have never been queer, yet queerness exists for us as an ideality that can be distilled from the past and used to imagine a future. The future is queerness’s domain.” When I first read this, I felt a resistance to it. I thought, “No—I AM queer!” Sitting more with my discomfort though, I start to find something generative in the notion that queerness might be this sense of reaching. I feel that reaching is an act of love not just for myself, but for community.

Since that afternoon I first encountered Peck, I’ve listened to hundreds of hours of his music. Sometimes on long drives to visit my partner and sometimes just sitting at my desk after reading poems. I drift immersed in his stories—stories of queer longing and power and heartache. Both his music and his use of the mask pushes me to consider queer temporality similar to what Muñoz suggests. And likewise, I feel some discomfort there. As recently as last week, I searched again for more about Peck’s background. The artist divulges snippets of his childhood and career in interviews, but I still have this urge to ask, “Who are you though?”

In the short documentary The Orville Peck Story, Peck talks about his use of a mask, saying, “I don’t think of myself as anonymous at all…. This is just an expression of who I am deep in my heart, and it allows me the freedom to be completely exposed and sincere.” I’m struck by that assertion against anonymity. It brings into focus the ways cis heteronormative culture frames truth as “facts” or tangible details. In the face of that, Peck frames realness as freedom, exposure, and sincerity.

This makes me think about how sometimes I regret having my name legally changed. Of course, having the change has made survival in capitalism much easier, but at the same time, I feel like I’ve given up something for the sake of being identified by the state. My name is tethered to my queerness because I chose it for myself, and I don’t want that to have to be pinned down.

The more I meditate on identity through Peck’s work, the more I find even parallels between what Peck is doing for the notion of queer futurity and Muñoz’s book Cruising Utopia. Muñoz explores scenes of “anonymous” queer sex, but in those scenes, he draws out feelings of euphoria and exposure. It prompts me to ask if “anonymity” for queer people is really often a resistance against being pinned down and defined by cis-heteronormative structures. In this way I think Peck’s mask is not only a source of “freedom” for himself, as he says, but it can also be seen as a source of freedom for us, the viewers. It’s a lesson in challenging our own notions of what it means to be queer and witnessed. What it means to share our love stories. I find Peck’s mask asking me what I asked of him, “Who are you?” Then, “Who are you becoming?”

ROBIN GOW is a trans poet and young adult author from rural Pennsylvania. They are the author of Our Lady of Perpetual Degeneracy (Tolsun Books 2020) and the chapbook Honeysuckle (Finishing Line Press 2019). Their first young adult novel, A Million Quiet Revolutions, is forthcoming in 2022 with FSG Books for Young Readers. Gow’s poetry has recently been published in POETRY, Southampton Review, and Yemassee. Gow received their MFA from Adelphi University where they were also an adjunct instructor. Gow is a managing editor at The Nasiona and the assistant editor at large at Doubleback Books. They live in Allentown Pennsylvania with their queer family and work at Bradbury-Sullivan LGBT Community Center.