The thing about being the murdered nanny is you set the plot in motion.

You had your own room there, and a bed with a pink cover, little purple flowers speckling it. You had a glitter-cover journal that you kept tucked under your pillow. They’ll find it when you’re gone — they’ll say gone, tell their children I’m sorry, she’s gone — the swirl of your neat little letters, the wish of your last entry: Someday my real life will begin.

Your room was beside the children’s; they hated the sound of airplanes at night and would call for you from their beds till you came to them and read stories from stiff-backed books, stories with little hens and fluffy sheep and talking cats. Stories with princesses and ogres and big bad wolves, your eyes going wide with the telling, their little eyes blink-blink-blinking away.

There, you’d say when the stories were done and the planes were landed, there, that’s better, that’s better now.

The children were small and you were pretty and you were young and you kept your door locked at night and your journal under your pillow.

She had an accent, the children’s mother will say when the detectives come round with their notebooks and their questions, templing her fingertips together as her husband stands behind her chair. He will lay his hand on her shoulder, the detectives will notice her slight flinch, the whitening of his fingertips. She had an accent. Not from here. Something foreign.

The children’s mother will hate your death, the messiness of it. It will remind her of something small and breakable in herself that she hasn’t thought of in a great long while. She’ll hate the weight of her husband’s hand on her shoulder, the chill she can feel through her silk blouse, she’ll hate the detectives and their notebooks and the sound of her own children crying, crying, crying for you.

She’ll call for the cleaning people to come in twice more a week, she’ll open windows wide to the brisk spring air.

It’s stuffy in here, she’ll say. Don’t you think it’s stuffy?

She will hire someone to replace you, someone to take your place, she will watch the empty chair at the dining table as if you will appear in it to cut the children’s food into smaller pieces, to spoon carefully-selected bites into their mouths, here comes the choo-choo train through the tunnel.

She will sit with her children in their bedroom when the planes fly overhead for their nightly landing, when they call your name first, before hers, her shoulders going tight at the sound of it. She will soothe them with tender hands on their soft and small cheeks.

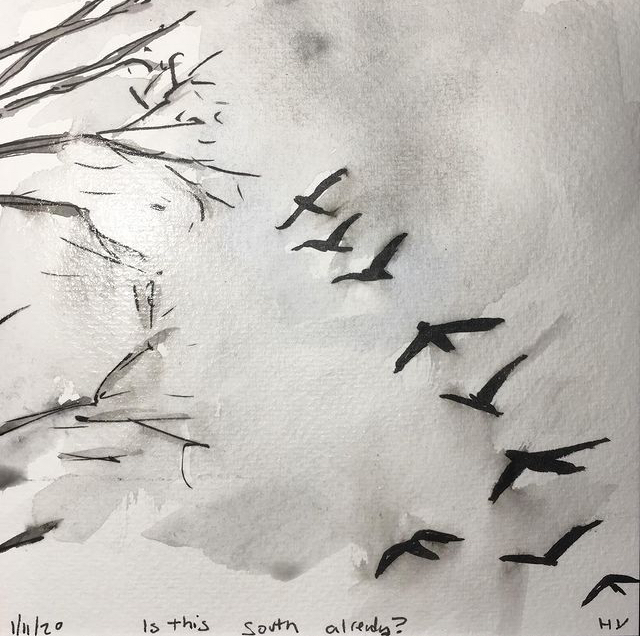

Shh, shh, she’ll say, shh, soon they’ll be gone, till her children’s eyes go flutter-flutter-closed, till the sky is empty, till the only house sound is the wind stirring through all the open windows and her husband’s sleeping breath from the bedroom where she has left him.

She will hire someone to replace you, she will call the agency, ask for someone blonde, someone plain, someone he won’t look at, someone none of them will look at.

She’ll lay the phone down on the counter, she’ll look again at the empty dining chair.

Oh, but she’ll still be young, she’ll say, cover her face with her hands, cover her eyes so she can’t see whatever trace of you remains. She’ll be so young.

One of CATHY ULRICH’S part-time jobs is to watch small children, which is her very best part-time job of all. Her work has appeared in various journals, including Adroit, Indigo Lit, and Juked.