Helen Frankenthaler was adept in the art of getting noticed. On May 19, 1950, she donned a costume meant to transform her into a Picasso painting and made her grand entrance into the Astor Ball flanked by an actress friend, Gaby Rodgers. Fresh from college and largely unknown, Life magazine found her eye-catching enough to take her photograph anyway—and have hers the only color photograph in the entire feature written about the event. Life would take her photo again, seven years later, in an article entitled “Woman Artists in Ascendance” which was focused on Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, Nell Blaine, and Jane Wilson. Yet Helen also made a cameo in the form of a full-page photograph of her against a backdrop of canvases bursting with shades of blue. In the same year, she appeared in an article in Esquire about the New York art scene.

Helen exuded style and confidence everywhere she went. She was the child of prosperity, whose male suitors were always prominent figures in the art world, and whose paintings brimmed with raw emotion and talent. However, they did not convey true suffering, in the way that many believed good artwork should. Hartigan’s harsh assessment of Helen’s art was that it looked like it was painted between “cocktails and dinner,” alluding to her wealth but also the lightness of the art itself, as if the lack of a sense of torture dimmed how substantial her work truly was. Hartigan later apologized, but she was not alone in her perception.

There’s a certain mythology that has been built up around Helen, which is not completely misguided but is not totally fair either. It’s true that you won’t find yourself in an abyss of anguish as you gaze at her work. She also never had to scrape by in order to survive, as many of her contemporaries did. But her life was not totally charmed, either. She went through childhood tragedy, devastating relationships, and episodes of depression that would plague her throughout her life. And even though she is beloved now, the sharp scrutiny of critics came around often, and Helen, no matter how confident she was in her talent, was not impervious to their sting. She had to earn her place in art history, and she wanted that place more than anything. And now, seven decades after the Astor ball, she is regarded as one of the most notable Abstract Expressionist painters of her time.

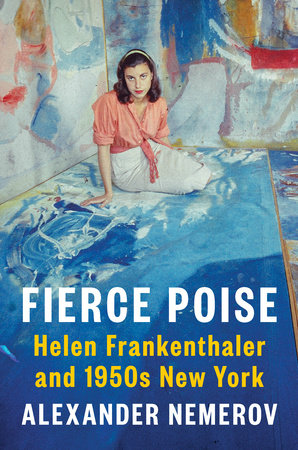

According to my online investigation, Helen Frankenthaler has never been the subject of a biography (I’m not counting Mary Gabriel’s Ninth Street Women, which was about several women within the AbEx movement and is also worth a read)—until now. Alexander Nemerov chronicles her life during the 1950s, along with a bit about her childhood and a flash-forward into after the ’50s, in his new biography entitled Fierce Poise: Helen Frankenthaler and 1950s New York.

Even though the book largely is focused on the 1950s, when Helen was in her twenties, Nemerov begins by describing her childhood in the Upper East Side. She was one of three daughters of a supreme court judge and began to exhibit a talent for art at an early age. She would pour red nail polish down the sink to watch the patterns it made and would draw a continuous chalk line on the sidewalk as she took walks with her family. Her childhood was happy, until tragedy struck: just shy of her eleventh birthday, her father passed away.

For the next several years, she experienced intense migraines and was convinced she had a brain tumor. She struggled in school, and eventually transferred to a more progressive school where she learned how to paint. This proved to be transformative, as the moment she learned how to paint she knew it was her passion. She went to Bennington to seriously study art and moved back to Manhattan after graduating to pursue her career as an artist. In 1950, she met the art critic Clement Greenberg, and they entered into a turbulent five-year relationship.

The 1950s would present a series of personal and professional challenges. Even with her talent and hard work, many critics misconstrued her work as being frivolous, instead of, as Nemerov describes them, as a “triumph over despair”. Her mother took her own life, which also caused tension between her and her sisters as they were divvying up their inheritance. Her relationship with Greenberg consisted of breakups and passionate rekindlings, and heartbreak became a constant companion. She worried that the access he gave her into the art world was a shortcut, rather than her entering it on her own terms. She craved individuality, which went from being an admirable personality trait into something that Greenberg resented greatly. He described her as having an “utter lack of delicacy” and being “coarse”. In 1955, they broke up for good, and soon after she found a new beau, the artist Robert Motherwell, who Helen was drawn to for his calm demeanor and mutual passion for art, and who she would eventually marry.

But despite all of this, the 1950s was also a revelatory time for her artwork: she saw a Jackson Pollock painting for the first time, which greatly influenced her art. She also developed her technique of staining raw canvas with striking splashes of color, a distinctive style she is still known for today. She began to get the attention she craved, appearing in articles in Life and Esquire, and found herself part of the rollicking, exciting movement that was Abstract Expressionism. And in 1960, she had her first career retrospective at the Jewish museum. Nine years later, she would have another career retrospective, this time at the Whitney. The book ends on this high note, with Helen’s legacy solidified in art history, her name poised to be forever known.

Along with telling her compelling life story, Nemerov also discusses how his own relationship with Helen’s art. Even though he had improbable connections with Helen throughout his life, including his father being her teacher and Bennington and Nemerov himself teaching at Yale, just a 45-minute drive from her Connecticut home, he spent most of his youth “not ready” for her. But it wasn’t just he who wasn’t ready—it was society at large. When he was in graduate school in the 80s, the general belief was that important art should be skeptical and ironic, which was something he believed as well. But as he got older, his attitude towards art changed, and in particular, his attitude towards Helen changed. This came about with age and experience, but this shift also occurred when he began teaching his students her work. He describes how he grew to embrace Helen’s art:

I abandoned my expertise. I let go of the skepticism I hid behind as a younger man. I left no scrim or safety net between me and the students, between me and the art, between me on the stage and the person I was alone. I began speaking— I don’t know how else to say it— as a person moved . . . I had either become the comfortable art lover I had once despised— effectively joining Helen in her solarium— or I had simply acquired enough perspective (in my own sweet time) to see that the world is made of hatefulness that deserves to be called out but also a kind of lightness and peace that are themselves ethical forces. The students seemed to like it for the most part. Evidently our capacity to be moved by art remains intact.

His interpretations and descriptions of her work are passionate and infectious, and Nemerov is perhaps at his best when sharing his own reactions to it. There’s a beautiful line where he describes her painting, Mountains and Sea: “[Mountains and Sea] suggests a search for a freedom so pure that it scarcely knows its own destination but trusts to the journey as a record, a monument, of unrestraint happening in real-time. In a world of regimentation and planned pleasures, Mountains and Sea dares to show life in a startling present tense— life on the wing.” He also compares her paintings to the Frank O’Hara poem, My Heart, which filled me with a joy I won’t even try to describe, you’ll just have to read it.

Along with offering rich descriptions and analysis that make you fall in love with her work, we also get an incredible story, one of turmoil and resourcefulness and utter determination. We get to learn about someone whose talent was undeniable and would eventually lead to the creation of timeless, inimitable artwork that is instantly recognizable and widely celebrated. Considering all this, it’s surprising that this is the first time someone has told her story. But is it really that unbelievable?

Sometimes I talk about my love of biographies about the female artists and writers of yore, and people will often assume that they are stuffy. Why spend time delving into the past, examining the lives of artists whose paintings now adorn notecards and calendars, when there are so many exciting things happening today? But there is something very contemporary about these books: that they just haven’t existed until recently. Maybe that’s stating the obvious, that we are finally celebrating overlooked women in history, that we are correcting our wrongs and giving overdue accolades to the creative women who always deserved it. But women finally being recognized will always be exciting to me. The fact that their stories have gone from being a footnote in art history to the subject of entire biographies speaks to the here and now, and it makes me hopeful about the future and all the stories yet to be unearthed.

Fierce Poise: Helen Frankenthaler and 1950s New York is published by Penguin Press and will be available March 23, 2021.

AYA KUSCH is an editor, artist, and freelancer based in San Francisco. She grew up playing with mud, which eventually led to a love of clay and a subsequent BFA in sculpture. She is fourth-generation Japanese and a third-generation potter, a Bay Area native, and a former bookseller who still obsesses over the best way to organize a bookshelf. She loves good design, contemporary art that will worry your mom and confuse your dad, and sculptures that make you look up. She is currently working on a book about art from Edo, Japan.