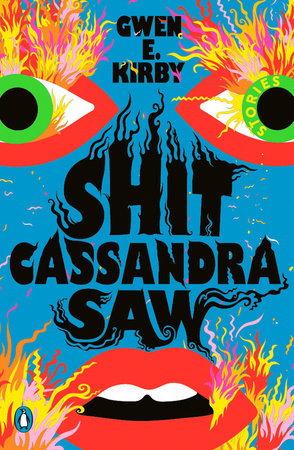

Two stories into Gwen E. Kirby’s debut collection, Shit Cassandra Saw, a woman bites off a man’s genitalia. She is on the subway when the man sitting beside her begins to masturbate. First comes the disbelief: This is really happening. Then she leans over and reveals a mouthful of fangs. She bites down and spits the flesh back out.

The casual violence of this scene is both shocking and darkly comedic—here is a woman who literally “bites back,” which is also an apt way to describe Kirby’s feminist project. Shit Cassandra Saw tells 21 stories about teenage girls, scorned ex-wives, and infamous warriors. This is a book about womanhood and the furious and reluctant ways in which women navigate patriarchal society. Kirby leaps in time, weaving in anachronism (like an ancient British queen who imagines herself as a professional baseball player) and fantasy (like a world where werewolves and Buzzfeed co-exist), and experiments with form, embedding stories within a Yelp review and instructions for retiling a bathroom.

In “We Handle It,” four teenagers encounter a “creepy” middle-aged man at a summer music camp. Kirby employs the first-person plural to unite the girls in their collective unease and rising panic. “We are swimming, and he regards us from the shore in that way we are learning to expect from a certain kind of man.”

Kirby’s younger heroines are only beginning to understand the patriarchal obsession with the body—the difficulties that girls face when “they haven’t learned to be cautious.”

The titular character, Cassandra, on the other hand, is “done, full the fuck up, soul weary.” When the Trojan priestess rejects the god Apollo’s advances, he spits in her mouth, cursing her with the ability to predict the future, but to never be believed. She understands her fate: Even if she shares her prophecies, the men will ignore her. Troy will fall. She will be sexually assaulted, forced to bear children, and later killed. Her body will no longer be her own. But Apollo’s spit is really “only spit”; like the other heroines in Kirby’s stories, Cassandra is condemned to live in a world where men dismiss her voice.

In “Here Preached his Last,” a mother reclaims her body from the burdens of marriage and motherhood by having an affair with her neighbor. “I’d learned that people cheated even when they knew they’d be caught. That sometimes getting caught is a form of defiance.” In a zany twist—a hallmark of Kirby’s storytelling—the mother is scolded by an 18th-century ghost preacher who follows her around whispering: whore, whore, whore. She relishes this reminder that she is being destructive and selfish. That she is finally using her body “for its own sake,” instead of straining to be a selfless mother and a morally pure, devoted wife.

“There are always things we will not do to save ourselves, ways we will and will not sell our bodies,” Kirby writes from the perspective of a 19th-century sex worker in a Welsh settlement in Patagonia. The heroines of Shit Cassandra Saw twist, mold, and reinvent themselves for protection. These are stories of self-transformation, where women carve themselves into “something good and new” to find fulfillment and safety.

The protagonist of “Marcy Breaks Up With Herself” imagines that she is a participant on a Marie Kondo-esque TV show, determined to become a different person in the process. “Why be a girl with an average face when I can be a wolfman?” An earlier story in the book, wryly titled “A Few Normal Things That Happen A Lot,” responds to this question. In a series of vignettes, women develop superpowers that allow them to exist without worrying about men catcalling or assaulting them. One woman receives fangs; another becomes a werewolf. Many are bitten by radioactive cockroaches, and their bodies turn into armor. These changes are mirrored in Kirby’s poetic language, where anything can be reimagined: Cardboard boxes are “cracked open like skulls”; a mouth opens “like a fish waiting for a hook.” Transformation creates a world where women feel safe. By taking on new identities in a society that wasn’t built for them, the heroines secure their own survival.

Still, the cockroach-women’s bodies burn and itch. The woman with fangs develops an abscess, bloody gums, and a sore tongue. “Women can never be emancipated from the stupidity of men,” remarks the protagonist of another story, a female doctor who is overseeing a duel between two women in 1892. Perhaps this is the point. Women’s emancipation from patriarchal violence requires sacrifice, a relinquishing of “some softer version of themselves.” If every means of escape from the patriarchy forces women to further change who they are, is that escape ever fully possible?

In the collection’s final story, four teenage girls gleefully stab a man to death. The tense moves from present to future, metaphorically emulating Cassandra’s divinatory power. Cassandra’s own fate may be tragic, but what she foresees for the women that will come next—tampons, epidurals, the cordless Hitachi Magic Wand—will bring them pleasure and relief. Now and then, Kirby offers her readers something similar, “a promise of better things to come” amid all the rage and violence in Shit Cassandra Saw. And in the absence of joy and hope, she imagines women who are recognizable in their frustrations and flaws, and she offers something even better: a familiarity that lingers.

ANGELINA MAZZA is a writer and fact-checker from Tio’tià:ke / Montreal. She is a poetry reader for Underblong and a recipient of the 2021 Chester Macnaghten Prize in Creative Writing. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Underblong, The Poetry Foundation’s VS podcast, THIS, Maisonneuve, and Cosmonauts Avenue. You can find her online @angejmazza.