“To describe anything / is to try and describe the divine”

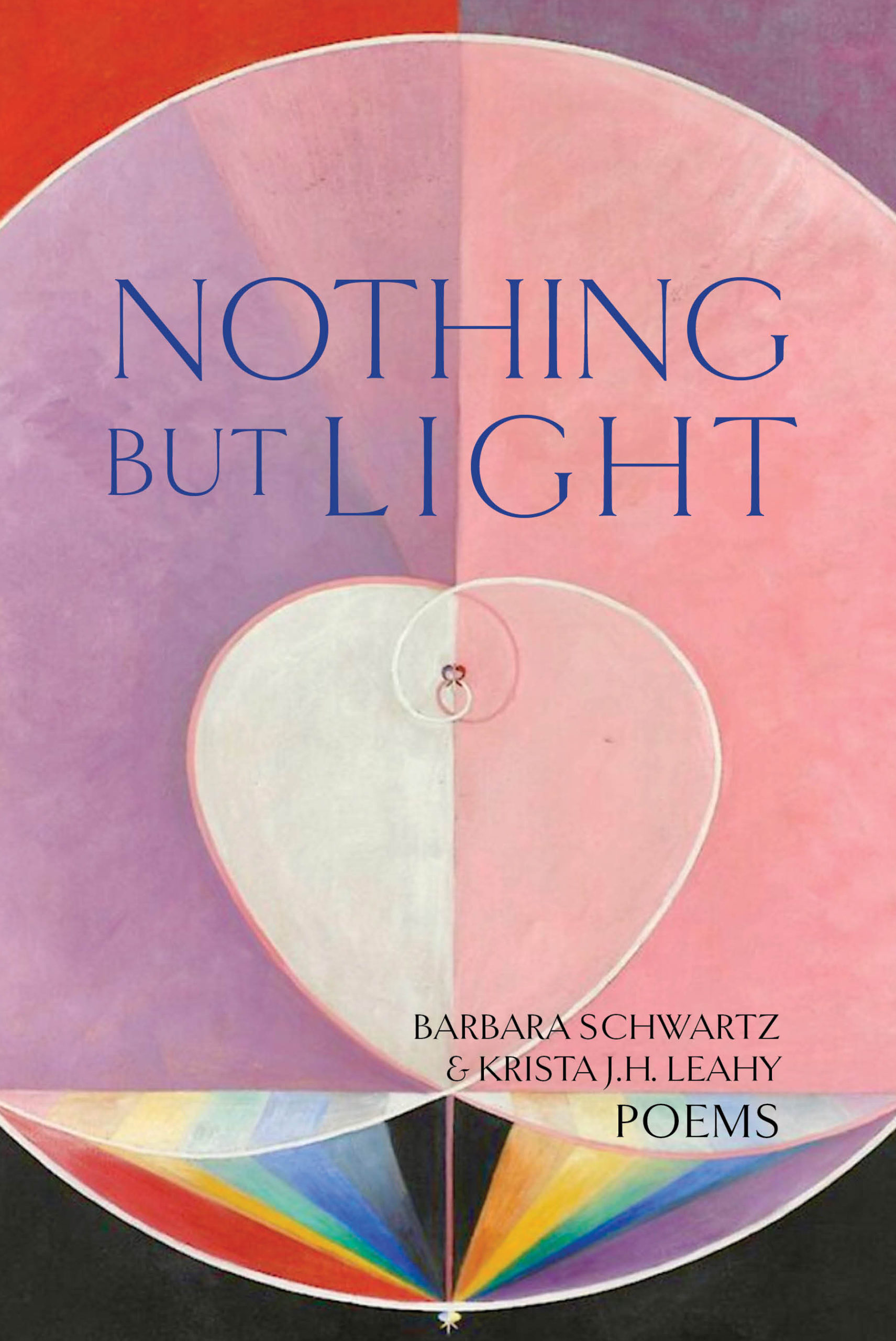

Barbara Schwartz and Krista J.H. Leahy’s collaborative collection Nothing but Light is a spiritual journey that merges the female body with divinity. The collective voices here sing the feminine as deity, demand it, and preserve it as so. The poems carry a storybook tonal element that shifts perspectives and rebuilds the idea of feminine power. “It’s a temple in here” and although the speakers don’t always know the prayers, they show readers that “In here God wants to be // a woman.”

Each poem carries an energy and fierceness to the line and isn’t afraid to ask questions. The book’s title comes from a series of questions in the poem “Of Two Minds:” “Must / a God suffer, hold weight, to be / a God? Might She hold / nothing but light?” In other poems too, there is an instinct pulling or encouraging readers into questioning themselves, learned ideas, and the world around us. This is what led me to understand these speakers were fearless—the female divinity they seek to find emerging from their own beings. Schwartz and Leahy instill this fierceness through moments such as “Hunger sneaks up // like two fingers flicking a pink / succulent moon” in “Empress of Ice Cream,” a response poem to Wallace Stevens’ “The Emperor of Ice Cream.” And later, in the poem “Moanday,” a truly priceless moment: “A lover said my breasts / were lopsided: I cupped his balls / like skinless grapes and said: both / small.” In my favorite poem of the collection, “Wholewhore,” we see a celebration of the female body and female pleasure:

she is mountainous, pendulous

every limb, protuberance, mound of flesh

bigger than the one before and all of it rocking

back and forth, back and forth , rock a bye baby and yes now please

legs open but no need for wide, no need to splay

to encompass the whole world until the whole world comes callingthis pleasure is hers

she seduces no one but herself

she is all of us, male, female, the loveliness in between

Joe Pan, author of Operating Systems, observed how “as the book builds a kind of generative path towards grace, where mythic ancestors (Gaia) converse with modern counterparts (Virginia Woolf), what’s exposed are deeply moving meditations—on cancer survival, on motherhood and the return of the prodigal daughter, on the regenerative properties of joy—guiding the reader to profound and unexpected places.” One of the most profound and unexpected being in the poem “Parable of the Prodigal Daughter”—I particularly loved this poem for its sudden surrealism. The poem begins with an ominous yet grounded image of a woman smoking American Spirits and watching “birds / smash into her windowpanes.” Then later, the woman steals “crows from the air, a mischief of mice from the stairs. / These caged pets formed her child’s torso. The legs she left / undone for fear of love’s departure.” A gutting image and that overwhelming fear of loss consumes readers when the woman refuses to give her reconstructed daughter legs. The poem specifies that we are in the woman’s dream space during this moment, but still, the deafening clarity of these images make it a tangible experience for the reader too: “In her dreams // her daughter returned. She wore a stained tunic, / a garland of weed, responded only to Saint Francine. / A frog curled around her ear, a snake around her arm. // She spoke in palindromes.”

The relationship between mother and child is a powerful thread throughout the collection. Schwartz and Leahy heighten the concept of a mother’s love to a godlike level, a level that equalizes mundane mothers and the earth itself:

Mother, sister, friend, daughter,

shake my hips, slake my lips,

slip me moon consort, for our planet toois round round as breasts, round as

bellies, round as roe, round as berry

go round, all fall down

Within these moments, we see the reality of a mother’s fear, longing, and willingness to sacrifice for her child: “What can I see and touch / now that the roots and wings and light / from the moths’ wings reside within / my cavity, my fertile grave agape, / with blood and bones sewing this / expanding body I call my own?” These moments validate the inner conflict mothers often face in feeling trapped by their families, their bodies, while simultaneously clinging to them out of fear of losing them forever: “What’s mine is / an illusion. My son’s not mine. He grows with time. My body’s no longer / a mine.” Equally so, Schwartz and Leahy remind readers of the freedom and power in birth, in life-giving. I appreciate the duality in these poems, how they address the “Devil tarot card” but leave us with “nothing but light.”

Throughout the collection, there is a struggle with the body, grappling with inability and illness, with mundanity, and these struggles are ultimately what propel or fuel the speakers’ journeys. We follow the two speakers to temples, “empty synagogues,” mosques, even a “Walking Crabapple Tree.” We learn from various Goddesses, Buddha, a tarot reader, a Shaman, and a sensei. These poems encapsulate a lifetime of spiritual and mortality challenges: “tightening my skin into / daylight doubt, duality, despair I pray // how can you love us so much yet not love us quite enough // and I do not know who I am / asking anymore.” There is intense vulnerability here and at the root of it all, a desperation for “scrubbing loneliness, nowhere and everywhere.”

The range in form throughout Nothing but Light is impressive and sufficiently engages the reader. From five-line poems like “Old-Timey Revolving Bathroom Doors” to four-page poems like “They Say You Are Everywhere” it’s exciting to see how unafraid Schwartz and Leahy are to use the page, how naturally their poems spread out, zooming in and out on this idea of woman. They teach us to “Learn and listen, smell and feel, this / world blooms when you recall all glistens / within you.” These poems are expansive and refuse to only be read once; they demonstrate and create the feminine divine, validate the tumultuous journey of finding and accepting it within ourselves; they explore a vibrant world in which women are seen. Let this book “woo the wildness of you.”

BARBARA SCHWARTZ is author of the chapbook Any Thriving Root (dancing girl press, 2017). A finalist for the 1913 Poetry Prize and the Barrow Street Poetry Prize and Alice James Award, her hybrid poetry manuscript “What Survives Is the Fire” was selected for performance at the 2023 Boomerang Theater’s First Flight New Play Festival at Congregation Beth Elohim. Her poems have appeared in Denver Quarterly, Upstreet, Nimrod International Journal of Prose and Poetry, Carolina Quarterly, Quiddity, Tinderbox Poetry Journal, and elsewhere. Barbara is an education consultant, with an MFA from Sarah Lawrence. She lives with her family in Brooklyn, NY.

KRISTA J.H. LEAHY’S poetry has appeared in The Common (Dispatches), Free Lunch, Raritan, Reckoning, Tin House, and elsewhere. Her prose has appeared in Clarkesworld, Farrago’s Wainscot, Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet, Year’s Best Science Fiction and Fantasy and elsewhere. She lives in Brooklyn, NY, with her family.

EMILEE KINNEY hails from the small farm-town of Kenockee, Michigan, near one of the Great Lakes: Lake Huron. She received her BA in Creative Writing and History from Albion College in Albion, Michigan and her MFA in poetry at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. Her work has been published in The American Journal of Poetry, West Trestle Review, Cider Press Review, SWWIM and elsewhere. emileekinneypoetry.com