Rightly dedicated to “Judas,” Kopano Maroga’s first collection imagines Jesus’s “lost years” as full of queer erotic bliss and newly vibrant prayers. In doing so, Maroga also weaves the voice of a more personal present-day speaker whose black queer self-celebration is a radical ritual.

The title poem, “jesus thesis,” begins, “jesus was a faggot / jesus liked it rough / jesus was a masochist,” establishing the speaker’s irreverently holy voice (14). The poem goes on as a litany of what “jesus was,” subverting the typical cis white straight depiction of jesus and summoning a queer and kinky image of jesus. I am intrigued by the use of the word “thesis” both in the collection’s title and this poem’s title. A “thesis” is often thought of as something kind of rigid and formal in an academic paper and in using this word pared with the poem’s rejection of conventional form and subject matter, the piece suggests formal conventions are not needed and in fact might hinder the exploration of transformative ideas like “jesus was a faggot.” The reclamatory use of the slur feels central to the poem. A word like “faggot” is jarring and to me, it seems to ask the reader to explore whatever comforts or discomforts the term might bring, overall suggesting this new framing of jesus will yield disruptive power.

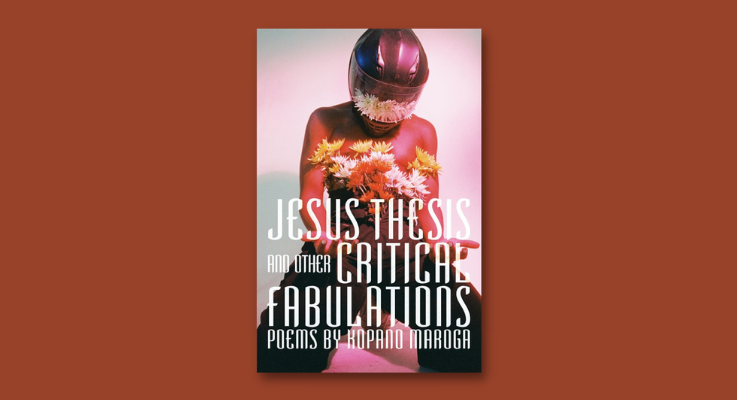

The ways these poems revolt against conventions bring out the themes of queer self-celebration and religious re-imagining. Most poems in the collection are in lower case and have their titles come at the end of the poem. I think specifically these two devices worked well in tandem to prompt me to re-read and continuously re-consider what the speaker is exploring. In a sense, these are queered poems both in their content and form. Another unique component of the book is the photographs of the poet and other visual art that act as sort of section breaks in the collection. These images assert the presence of the poet between their words, often depicting the poet in tender or intimate positions in a bathtub or with flowers. Then, sometimes, the images are visual art like one where a man sucking dick is spliced into a renaissance painting of Jesus. I felt like the visuals are working towards the same effect as the poems’ forms; they are equal parts expression of self-tenderness and generative contradictions.

These poems are a lesson in repetition’s myriad uses; Maroga skillfully weaves pieces of Catholic prayers and his own refrains to create juxtapositions and a language of queer longing and grief. In “morning eucharist” the repeated “holy” at the start of each line accumulates and creates a sense of hunger or yearning, inverting how “holy” might be used in prayer to highlight actions or people to praise. The last line of the first stanza reads, “holy help me make it through another day” the speaker goes from listing struggles to, in one line, reaching towards a divine (18). I think the book answers that call and suggests that the divine is not the Christian one, but a flourishing within the self. This sense of urgency in these poems reminded me of a lot of the poems in Richard Siken’s Crush. The use of holy language for amplifying queer eros and sacredness felt in conversation with the work of Mark Aguhar and Jericho Brown’s The New Testament.

In poems like “in my mother’s garden” Maroga also uses a refrain to amplify familial grief and abuse connected to queerness. The repeated “my mother used to grow roses!” connects the mother to the symbolism of the Virgin Mary as the speaker talks dually as Jesus and potentially a speaker that feels closer to the author from adjacent poems. The repetition reinforces the mother punishes the son’s queer embodiment and thus nothing grows in the garden. Maroga also uses the refrain “where do we begin” in the poem “it’s been so long,” to find queerness in his South African heritage. They write, “in the languages of my mother’s and / father’s tongues there is no pronoun for / he or she / only: you / only: them / only: me” finding trans flourishing in that ancestry (77). “it’s been so long” also examines the suffering and grief caused by centuries of colonization and perpetuated by white queer people to the speaker.

In the end, like the flowers bursting from a figure’s torso on the book’s cover, the word “bloom” comes to mind to describe the speaker and reader’s journey through Jesus Thesis and Other Critical Fabulations. Amid a society and religion that condemn a queer body, Maroga makes those words and images burst with lush queer desire. The poem “someone i love asked me for the definition of humidity / and all I got was this unshakable grief” on page 54 begins,

the blossom knows not the violence

it has done unto the bud

this is what it means to bloom

to rupture that which you were

before your

b l o o m i n g

I interpret this as a queer/trans manifesto on self-acceptance and self-honoring where the bud is venerated for what it had to do to yield the flower, the present self. This is a collection that ends on praising the holy black queer self and revels in that body’s joys and divine force.

KOPANO MAROGA was born in Benoni in 1994. They are a performance artist, writer, cultural worker, and co-founding director of the socio-cultural arts organization any body zine. Currently, they are working as a curator and dramaturg at Kunstencentrum Vooruit in Ghent, Belgium. They believe in the power of love as a weapon of mass construction.

ROBIN GOW is a trans poet and young adult author from rural Pennsylvania. They are the author of Our Lady of Perpetual Degeneracy (Tolsun Books 2020) and the chapbook Honeysuckle (Finishing Line Press 2019). Their first young adult novel, A Million Quiet Revolutions, is forthcoming in 2022 with FSG Books for Young Readers. Gow’s poetry has recently been published in POETRY, New Delta Review, and Washington Square Review.